Arthur Chin – Chinese American Ace

In the early morning of August 3rd, 1938, over 70 Japanese A5M fighters escorting 18 Mitsubishi G3M Bombers (type 96) of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) were detected to be in route to Wuhan, China. The Japanese and Chinese had been fighting an undeclared war since July of 1937 when Japanese Army forces invaded North China. By July of 1938, China had lost much territory in the North, its great port of Shanghai, and its capital, Nanjing (Nanking). Instead of suing for peace as the Japanese military was hoping, the Chinese government under Generalissimo Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-Shek) moved the capital to Wuhan – the 2nd largest Chinese city at the time. The IJN had been bombing Wuhan since Feb of that year and as the Chinese Air Force defended its new capital, the largest air battles in China were being fought over her skies.

In the early morning of August 3rd, 1938, over 70 Japanese A5M fighters escorting 18 Mitsubishi G3M Bombers (type 96) of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) were detected to be in route to Wuhan, China. The Japanese and Chinese had been fighting an undeclared war since July of 1937 when Japanese Army forces invaded North China. By July of 1938, China had lost much territory in the North, its great port of Shanghai, and its capital, Nanjing (Nanking). Instead of suing for peace as the Japanese military was hoping, the Chinese government under Generalissimo Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-Shek) moved the capital to Wuhan – the 2nd largest Chinese city at the time. The IJN had been bombing Wuhan since Feb of that year and as the Chinese Air Force defended its new capital, the largest air battles in China were being fought over her skies.

By 10 AM, the Chinese Air Force’s mixed bag of 20 Russian I-15bis, 13 I-16s, 7 American Curtiss Hawk IIIs, and 11 British Gloster Gladiators rose up to intercept the Japanese. One group of 7 Gladiators and 3 I-16s were led by 24 year old Captain Chin Ruitian (Chin Shui-Tin), commander of the 28th Pursuit Squadron. While the main body of the Chinese fighters soon made contact with the Japanese, Captain Chin’s group flew in a more South West direction. They soon spotted 30 A5M’s 2000 feet above them and Chin tried to bring his group up to 21,000 feet to gain an advantage. However, the A5M saw the Chinese fighters and dived onto them as the Chinese were climbing. Chin’s wingman soon found an A5M on his tail, Chin in turn followed the A5M and was able to drive the Japanese off. He was immediately attacked by other A5Ms with bullets striking from behind. Luckily, Chin had just installed some armor salvaged from a Russian fighter behind his seat the previous day.

While Chin desperately made evasive turns, 3 A5M’s were taking turns making diving passes at him and then zooming back up to altitude again, using the planes superior speed and power. Chin soon found it difficult to control his plane as it took more and more damage with each successive pass. Knowing that his plane was lost, Chin waited for the next A5M to come out of his dive and made a tight turn in an effort to ram the Japanese. His top wing and the A5M’s tail was sheared off, causing the A5M to crash and his Gladiator to spin out of control. Chin was dazed from hitting his head at the impact of the ramming, but he was able to parachute out of the spinning Gladiator.

As the story was told by Capt. Royal Lenoard – personal pilot to Jiang Jieshi at the time – in his 1942 memoirs “I Flew For China”,

He (Chin) examined the remains and found one machine gun undamaged. With this gun over his shoulder he walked eight miles back to his base. There he met Chennault. Before Chennault could say anything Chen held out his machine gun in both hands. “Sir,” he said, “can I have another airplane for my machine gun?”

The same story was related by Claire Chennault in his memoirs “The Way of a Fighter”. This was of course before Chennault gained fame as the head of the American Volunteers Group or Flying Tigers. At the time, he was technically a consultant for the Chinese Air Force in charge of Nanjing air defense.

A good story, but as Chin would later relate – After getting to the ground safely, he salvaged the machines guns and was able to fly back to his base in a Douglas O-2MC where he checked into the base hospital. It was there that Chennault visited him and Chin jokingly asked for a plane to go with the guns. Chennault had never learned Chinese, so Capt. Chin spoke to him in fluent English. Better known to his friend as Arthur Chin, like Chennault, Chin was an American citizen who came to China to help fight the Japanese. Chin’s father was Chinese and his mother was Peruvian. He was born and raised in Portland, Oregon.

During the early 20th century when the last Chinese emperor was overthrown, China was controlled by different warlords, each having his own fiefdom. The Western powers had their own independent areas within the major Chinese ports, Shanghai being the biggest and most famous. Unlike China, Imperial Japan was able to revolutionize its military and industrial complex to successfully challenge the Western powers. That was made clear to the world when it soundly defeated the Russian Eastern fleet at Tsushima during the Russo Japanese War in 1905. By the late 1920’s, Japan would join the Western powers in the game of imperialism, with its weak next door neighbor, China, as the prize.

At the same time, the rise of the Chinese Nationalist (Guomingdong) would nominally reunite China in the 1929 as its army marched from Guangdong (Canton) in south China up to the old Capital of Beijing (Peking) in the North. While the Nationalist had the largest army, its conquest succeeded as much by bribery and payouts to the different warlords as by military might. Many of the existing warlords became ‘governors’ and their allegiance to the Central government was tenuous at best. In addition, a virtual civil war was being fought between the Nationalists and the Communists.

It was against this background of a resurgent Chinese nation that ultra right wing militarism was to gain ascendency in Japan. By 1932, Japan had wrestled away Manchuria in the North away from China and formed the ‘Manchukuo’ puppet government under the old disposed Chinese emperor. Japan would continue to annex territory from North China as the weak Chinese government tried to buy time and gain the world’s sympathy. This situation created a ground swell of support by oversea Chinese for their traditional homeland. In the United States, local citizens and the Chinese government appealed to the Chinese-American community for monetary support. One area that garnered support was the role of Aviation as a quick way to modernize the Chinese Army to defend against the invaders. Money was raised not only to buy American aircraft, but local youths were enrolled in flying schools as eventual volunteer pilots for China.

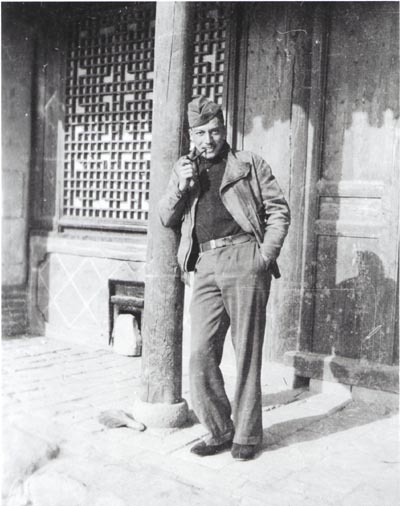

Arthur Chin was born on October 1913, and at 19 years of age he was taking flying lessons in Portland, Oregon. After the Japanese annexation of Manchuria in 1932, he and 13 others who trained with him sailed for Shanghai. After landing in China, they weren’t certain of their status with the Nationalist government. One of the largest Air Force in China at the time existed with the Guangdong Warlord, Chen Jitang. Arthur and his group eventually arrived in Guangdong and he soon became a Probationary Warrant Pilot in the Guangdong Air Force. By Feb of 1933, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant. Looking at his picture from that period, he cut a dashing image in his uniform, smoking a pipe, and sporting a thin mustache much like that of Errol Flynn or Clark Cable.

While Chin was in Guangdong, Americans under retired US Army Air Corp Major John Jouett provided training and aircraft to the Nationalists via the Central Aviation School. Another air mission under Edward Deeds set up the Canton Aviation School for the Guangdong government with four American instructors. Unfortunately, Deeds was to die in a flying accident in July of 1933. Aside from trainers, one of the first American fighters sold to the Guangdong Air Force was the Curtiss Hawk II after a demonstration by James Doolittle. Doolittle was an Air Corp reservist at the time and flying demonstration flights for the Curtiss company. This is the same Doolittle who would gain international fame with this B-24 Tokyo raid years later. Between 1933 and 1936, approximately 150 pilots graduated from the Canton Aviation School and the Canton Aviation Factory was set up in Shaokwan.

During his stay within Guangdong, Arthur Chin met a Miss Ng Yuetmei, a government diplomat’s daughter who was studying there at the time. Like Chin, she grew up overseas and they both soon married, eventually having two sons. However, she would not survive her time in China as she would later be killed in a Japanese air raid.

In June of 1936, the Guangdong and Guangxi warlord broke with the Central government. While Guangxi leaders were after a tougher anti-Japanese action, General Chen as simply out for more power. Jiang Jeshi was able to out-maneuver and bribe his way out of the situation. After a few minor clashes, the whole Guangdong Air Force defected over to the central government. Other Guangdong generals followed suit and Chen was soon on his way to Hong Kong where he had stashed millions away. With the defection, the Canton Aviation School merged with the Central Aviation School. Arthur Chin was now part of the official Chinese Air Force as he originally intended when he sailed for Shanghai.

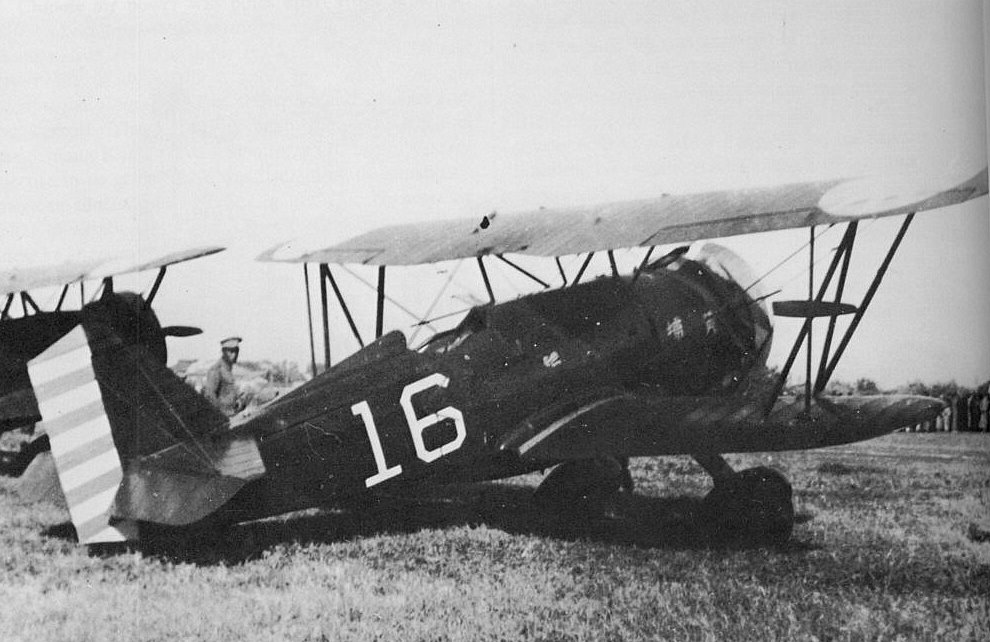

(photo: Jano from canton1933 – line up of Hawk IIs in Canton)

(photo: Jano from canton1933 – line up of Hawk IIs in Canton)Like the Americans, the Germans and the Italians also had sent military missions to the Nationalists at the time. The German Advisory Mission (Deutsche Beraterschaft) led by retired General Von Seeckt was later replaced by General Alexander von Falkenhausen. Besides training ground troops, selling weapons, and German aircraft, the mission set up a flight training program. Arthur was to benefit from this as he and 6 other pilots were to receive fighter training in Germany in 1936. This was most likely at Luftwaffe fighter pilot school in Schleissheim, Munich. He returned to China in September of that year and was promoted to First Lieutenant and 6th Squardon flight leader. By June of 1937, he was the vice Commander of the 28th Pursuit Squadron – 5th Pursuit Group, flying the Curtiss Hawk II.

Photo courtesy John Gong – With fellow trainees in Germany

Photo courtesy John Gong – With fellow trainees in Germany

Photo courtesy John Gong – Surrounded by German Luftwaffe personnel

Photo courtesy John Gong – Surrounded by German Luftwaffe personnel

Within a few months, an Incident with a missing Japanese soldier at the Marco Polo Bridge in Northern China would precipitate a general Japanese invasion of China. Both the Japanese and Chinese accuse each other of unprovoked firing with the Japanese claiming that one of their soldiers was kidnapped. The Japanese Kwangtung army immediately mobilized its forces. The return of the Japanese soldier from what was apparently a drunken outing the previous night did not stop the Japanese demands of Chinese territory or a pullback of Chinese troops. Unlike the previous 5 years of weak Chinese response to Japanese encroachment, Jiang Jeshi decided to fight.

By August 13, Generalissimo Jiang, in an attempt to draw international support, would challenge the Japanese in the South at Shanghai, where large American and European settlements were located. Sending his best troops into the area, the Japanese Navy would respond with Marine landings and the arrival of aircraft carriers Hosho, Ryuj, and Kaga. (The same Kaga that would be sunk by Americans in the battle of Midway). They also moved the Shikaya and Kisarazu squadrons to Taiwan, allowing them to strike the Chinese airfields around Shanghai and Nanjing. The next day, Japanese bombers would raid the nearby city of Hangzhou and its training fields, where the Chinese Air Force (CAF) challenged them with Hawk II and Boeing 281s and was credited with downing three of the Mitsubishi Type 96 (G3M) bombers.

Claire Chennault who had recently arrived in China, was given the role of planning the Air offensive around Shanghai. Chennault had already toured all over China to evaluate the Chinese Air Force in the previous months. At the end, his report gave a grim picture – an air force equipped with mostly antiquated biplanes and flown by many pilots who received wings based more on connections than on skills. Particularly damning was his opinion of the Italian delegation that ran a flight school which gave 100% passing rate for the pilots and keeping destroyed planes on the official roll. When the fighting started, the Italian mission packed their bags. Meanwhile, the Japanese Navy and Army had a strength almost three times that of the approximately 250 serviceable aircraft in the Chinese Air Force.

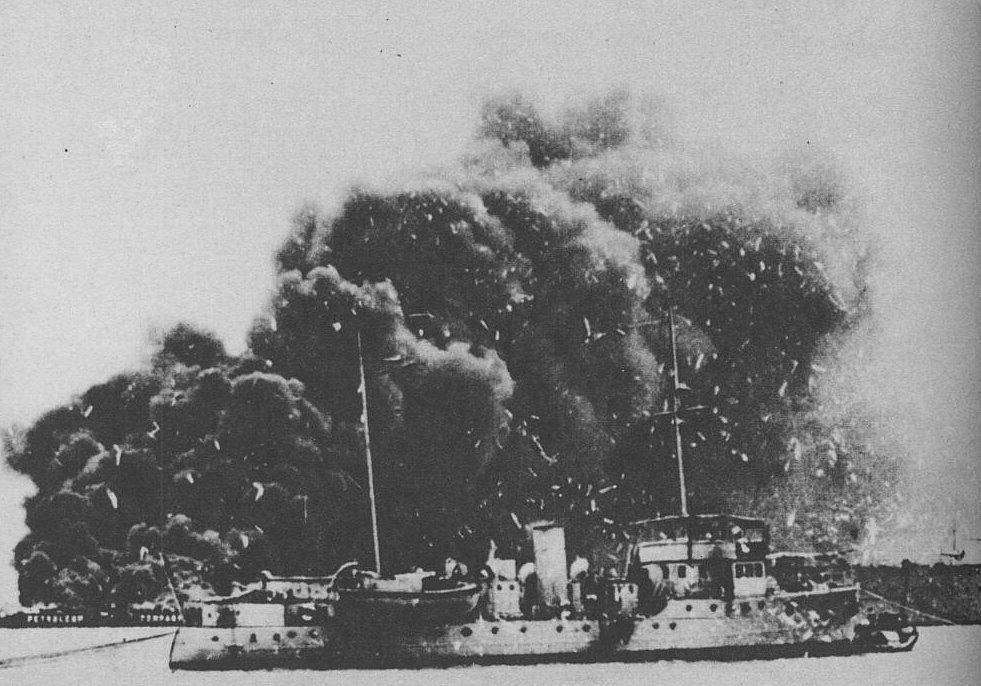

(Photo- Chinese bombing raid on Shanghai Harbor

(Photo- Chinese bombing raid on Shanghai Harbor

Chennault had the Chinese pilots practice both dive bombing and level bombing. On August 14th , they would be sent out to the Shanghai harbor to strike the Japanese fleet. The Curtiss hawks achieved limited success against the Japanese marine headquarters and Japanese cruisers with dive bombing. The attack against the Japanese flag ship, Idzumo, would turn into a disaster. Chinese Northrop bombers were to have bombed at 7,500 feet, but instead, they bombed at 1,500’ due to heavy cloud cover. Without adjusting their bombsights, the bombs hit the Palace hotel and Nanjing Road, the main thoroughfare in Shanghai. Over 3,000 civilians were killed and wounded.

(Photo – Japanese flagship Idzumo in Shanghai Harbor)

(Photo – Japanese flagship Idzumo in Shanghai Harbor)

The Japanese Navy Air Force objective at this time was to neutralize the Chinese Air Force by bombing the Chinese airfield and to demoralize the enemy’s will to fight. To protect the airfields and the Chinese capital, Nanjing, Arthur’s squadron was moved to nearby Chu Yung airfield. On August 16th, the Japanese launched two raids against this airfield from Taipei, Taiwan. The 28th Pursuit Squadron was scrambled with Chin in his Hawk II. Also getting off the ground were the 17th PS Boeing 281 (export versions of the P-26) led by fellow Chinese American pilots John Wong and ‘Buffalo’ Wong – both of whom were originally in the Guangdong Air Force along with Chin. The first six G3M’s had already dropped its bombs on the airfield as the 17th PS was rising up to the bombers. Catching one of the G3M’, the John Wong was able to attack it from behind and send the bombers down in flames. Turning back, Wong along with another pilot attacked the lead G3M, sending that plane to crash near the airfield. By this time, Arthur was after another G3M that had just released it bombs. He was able to hit the G3M multiple times from the rear, but his slow Hawk II could only maintain its distance against the bomber. The Japanese rear gunner was, in turn, able to shoot up Chin’s plane, hitting the engine and fuselage. After trailing the now smoking bomber, Chin decided he needed to get his own damaged plane back. He was able to crash land to a secondary airfield and was credited with a kill. However, unbeknown to the Chinese, the G3M was eventually able to reach a Japanese air base in Korea and crash landed.

(photo CAF Hawk III at whaompoa)

(photo CAF Hawk III at whaompoa)

Chennault by this time had set up his warning net using a network of spotters and field telephones, giving time for the Chinese fighters to intercept incoming bombers. By the end of August, the Japanese had lost over 50 planes, at least 29 of which were bombers. Like the US and Europe would realize a few years later, the myth of the invincible bomber unescorted by fighters was shattered. This was graphically illustrated by a raid on the 17th when twelve B2M1 torpedo-bombers (Type 89) took off from the Kaga to raid the city of Hangzhou. (Interestingly, the B2M1’s were designed by the British firm Blackburn for the Japanese in 1929). The bombers failed to rendezvous with the escort fighters and flew on alone. Only one of the bombers returned to the carrier after being intercepted by Chinese fighters. After this series of devastating loses, the Japanese temporarily stopped the bombing attacks to in order to regroup. They would return with either unescorted night bombings or all daylight bombing missions were to be escorted by fighters.

The Chinese continued with their own bombing missions against Japanese ships in Shanghai with limited success. This included a mission where five Heinkel He111 were used, 3 of which were shot down by the Nakajima Ki-27 fighters.

In September, the 28th PS was split into two. The first group flew to the North while Chin’s group was sent to Shaokwan airfield in Guangdong to defend the nearby aircraft factory. On the 27th, Chin led his four Hawk II’s along with another group of Hawk III’s to intercept 3 G3Ms. One of the G3Ms was damaged by a Hawk III and then was attacked again by Chin. Two of the gunners were wounded and the plane’s fuel tank was hit. The bomber eventually ditched into the ocean but most of the crew were rescued by a British ship.

By October 1937, aircraft losses mounted for the Chinese. Unlike the Japanese, who had similar losses, China had almost no indigenous aircraft design program. The aircraft factories that she did have were meant for aircraft assembly and not production, China desperately needed to get replacements from abroad. Orders were placed for replacements in France, US, and the UK. Delivery though, would not be until end of the year at earliest. Meanwhile, the Russians had signed a non-aggression treaty with China and was ready to ship war material and men immediately. Approximately 450 Russian volunteer pilots and crews along with over 200 aircraft would be sent to China in October. These included 62 Poliparkov I-16 monoplanes, 93 I-152 (I-15bis) biplane fighters, and Tupolev SB light bombers.

From the French, a batch of Dewoitine D.510 monoplanes was ordered. From the British, a major purchase was sent to buy 36 Gloster Gladiator Mk. Is. These started arriving on November 1937 at Kai Tek Airport in Hong Kong. The Chinese then sent the unassembled planes on by rail and boat into Gunangzhou. Despite Japanese bombings, the planes were assembled by January of 1938 and along with the 17th and 29th PS, Arthur Chin’s 28th’ PS was the first to receive these machines. Shanghai, along with Nanjing by this time had fallen to the Japanese Army. The Chinese capital was moved west to Wuhan.

Chin’s first success came in May when the IJN sent a flight of Nakajima E8N1 (Type 95) floatplanes from the carrier Kamikawa Maru on a bombing mission. Receiving warnings from Chennault’s air raid network, Chin led 4 other 28th PS Gladiators from Nanchang airfield to intercept. At 7,500 ft over the city of Hukou, Chin spotted the nine Japanese bombers 1,000 feet below them and signaled his fighters to attack. Diving from above, the Gladiators repeatedly tore through the IJN planes, scattering them as they tried to shake off their attackers. Chin was able to shoot down one of the floatplanes, killing both the pilot and observer when the plane crashed. Soon after this action, Chin was promoted to Captain and commander of the 28th PS in June.

Within a few weeks of his promotion, Chin was to claim another two Japanese planes. On June 16th, Commander of the 5th Air Group, John Wong, led by Chin and 7 other Gladiators to intercept Japanese bombers. Catching the six G3M at 11,000 feet and with a 2,000 feet height advantage, the Gladaitors dove into the bomber formation. John Wong dove pass the lead bomber and turned back up to attack the lead bomber from underneath. Hitting an external bomb, the lead bomber exploded. Chin was right behind to shoot the 2nd bomber until it caught fired and crashed. Three other bombers were also claimed by Chinese pilots, but Japanese records seem to indicate these planes returned safely despite sustaining heavy damage. Arthur had hardly returned to base when the Air Raid network spotted one of the G3M’s that had been separated. He immediately took off again and was able to intercept the bomber. He attacked the enemy and had last seen it smoking, but with his ammunition exhausted and low on feul, Chin had to fly home. Despite only claiming that he damaged this plane, Japanese records show that this G3M eventually crashed. Two of the Gladiators were lost during this sortie.

The fighting around Wuhan in August of 1938 would be a major campaign by the Japanese to attempt ending the ‘China-Incident’. The Japanese general staff had severely underestimated the Chinese will-power to resist even after the capture of its main ports and its capital. They also underestimated the amount of men and material they would need to commit to China to keep its gains. It would be 5 months of bitter fighting before Wuhan would be taken. The decisive victory the Japanese were looking for would still elude them as the Chinese moved their capital even further west to Chungking and vow to fight on.

It was during the Wuhan campaign that the Japanese would attempt to stop supplies reaching China from Guangdong by bombing and an invasion of land forces. Hence the reassignment of Arthur to Guangdong in August. On the 2nd of that month, Chin had armor installed behind his Gladiator (#2806 or #2809) and as noted previously, this most likely saved his life when he was attacked by A5M’s the next day. Chin would claim his 4th kill by the ramming of the A5M. After this action, Arthur along with the 28th PS were reassigned to the 3rd Pursuit Group.

By 1939, even though the Japanese had effective air superiority over much of China, they were still harassed by Chinese fighters. At that time, the Japanese air strength had been increased to over 900 aircrafts while the Chinese were down to only 135 fighters. By now, only six Gladiators remained operational, Chin and the Gladiators were moved to Liuchow in Kwangsi province for repairs, while other pilots transitioned to Russian fighters. It was here that they carried out a ‘guerrilla campaign’ against the Japanese – harassing the enemy while avoiding any major confrontations. In October, Chin led the 28th PS in intercepting a flight of Nakajima B5N, where he shared a kill of the Japanese planes. On Nov 2nd, he and his wingman attacked and damaged a lone IJN Type 98 C5M reconnaissance plane. Chin was able to injure the defending rear gunner but his wingman was unable to bring the aircraft down.

In December, Chin was promoted to Major and deputy commander of the 3rd Pursuit Group. A few weeks later before Christmas, Chin was to make his final claim on a twin engine bomber. On the 27th of that month, Chin went on his last mission. Flying his Gladiator, along with an I-15 and another Gladator, Chin was escorting a flight of 3 Russian crewed SB-2 bombers on a mission over Kunlan Pass. They ran into agroup of A5Ms from the 14th Kukutai over Yunping. The I-15 was damaged and the pilot was wounded, forcing the plane to land. Chin had just claimed an A5M when he noticed the second Gladiator was being tailed by another A5M. Chin moved behind the Japanese in an attempt to shoot him off. It was too late, the first Gladiator was destroyed and before Chin could pull away another A5M jumped on him and fired into his fuel tank. His Gladiator was immediately engulfed by flames and soon Chin was also on fire. Chin managed get his plane over to Chinese lines before unstrapping himself and parachuting out at 3,000 feet while a Japanese fighter shot at him. He slumped over and played dead in an effort to evade the Japanese. He was able to make it to the ground but was severely injured with severe burns to the hands and face. Chinese soldiers were able to rescue him, but he wasn’t evacuated to a hospital for another 3 days. This final sortie would ended his fighter career as an Ace, with 2 claims while flying the Hawk II and 3.5 claims while flying the Gladiator, with another 3 unofficial kills.

Chin would eventually be sent to Hong Kong for medical treatment. He would then make it back to the United States for plastic surgery and recovery. During five long years of rehabilitation, he married his nurse, Francis Murdock. In 1945, Chin was discharged after successful rehabilitation but would become permanently disfigured with burn scars on his face and hands. He and Francis divorced when Chin decided to return to China to fly supplies on C-46 and C-47s over the hump with the China National Air Corp (CNAC). While working in China, he would meet his 3rd wife, Yang Ruizhi (Vivian), a fellow CNAC employee. They were married in 1948.

(photos courtesy John Gong – Chin flying the hump)

(photos courtesy John Gong – Chin flying the hump)

Eventually in 1950, after the Chinese civil war ended with the Communist controlling the mainland and the Nationalist withdrawing to Taiwan, Chin decided to come home to Oregon with his new wife. Like many ex-military pilots, he was unable to find a job flying back in the United States, so he worked for the US post office. He would eventually have another son who went on to work in the US Diplomatic Corp in Singapore.

Arthur Chin eventually retired from his post office. In 1995, the US Government awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross, thus recognizing him as a US veteran. Arthur Chin job passed away in September 1996. In October of 1997, he was honored as one of the first seven Americans inducted into the American Combat Airmen’s Hall of Fame. An Arthur Chin Aviation Achievement award was named in honor of him by the Sino-American Aviation Heritage. Most recently in May 2008, the post office at Beaverton, Oregon where he worked, was renamed the “Major Arthur Chin Post Office”.